Early Notification Scheme Progress Report: collaboration and improved experience for families

The NHS has published a report this week that outlines the first year of their ‘Early Notification Scheme’ for babies with potentially severe brain injury sustained in the context of childbirth. The aims of the scheme are to provide support to families and begin investigations into the likely cause much earlier than has occurred in the past. Investigation of these rare but severe incidents will identify where the standard of health care has not met expected standards. Although obstetric litigation is only 10% by number, it accounts for 50% of the total value of new claims reported.

NHS hospitals are required to report to the ENS team within 30 days, all babies born at term with potentially severe brain injury diagnosed in the first 7 days of life, specifically those falling into the categories:

Was diagnosed with grade III hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy (HIE) or

Was therapeutically cooled (active cooling) or

Had decreased central tone AND was comatose AND had seizures of any kind

The ambition of the scheme is not only a proactive investigation of liability but also to encourage open conversations with families about incidents and to maximise learning by the healthcare service as a whole. Collating a 100% notification database would provide valuable insights into what causes these incidents.

The first report describes a number of clinical themes, as well as recommendations in areas relating to the handling of these traumatic incidents - for both families and staff involved. These are the headline statistics (April 2017 to March 2018):

640,000 births

808 incidents reported

746 qualifying cases (0.12% of all births)

197 cases involved NHS-appointed solicitors and clinical teams in an accelerated liability investigation process

24 admissions of liability, a formal apology and in some cases financial assistance with care and other needs within 18 months of the incident

Clinical feedback is provided to hospitals, with information to share with families.

Analysis of themes

The report describes an analysis of 96 of the total 197 cases where the hospital or clinical review classified the case as likely to have involved substandard care, or where the family had instructed solicitors.

Delay in birth

Avoidable factors included:

1. An assumption that the loss of fetal heart recording is an equipment failure

2. Bradycardia in the late second stage, where the team expected the baby to be born ‘any minute’, when in reality the birth could have been expedited, reducing the duration of hypoxia

Other important factors in relation to delay:

Delay in achieving analgesia

Delay in after-coming head at vaginal breech birth

Issues with availability of theatre

Team communication problems

Fetal monitoring

70% of cases were linked to fetal monitoring issues and importantly as a single factor, this was rare. Two-thirds had 2 or more adverse factors in addition: the most common was a delay in acting on abnormal/pathological CTG or IA; delay in escalation; incorrect classification. This is not just about clinicians reading CTGs incorrectly:

‘...understanding what can go wrong when electronic fetal monitoring is used requires full characterisation of the work and social practices involved, the multiple professions who conduct such practices, and the context where the process takes place.’

Difficult delivery of the fetal head at caesarean section

This is an emerging problem both in the UK study and in international reports. It occurred in 9% of this sample. Conversely, shoulder dystocia complicated 12% of vaginal births in the cohort. There are established training and management protocols for shoulder dystocia, but not for the impacted head. This is an identified area in need of attention.

Maternal deterioration in labour and hyponatraemia

In this cohort, 6% of mothers experienced a concurrent medical emergency. In particular, significant maternal hyponatraemia (serum Na<130 nmol/L) appears to be an emerging issue in labour, with concurrent hyponatraemia in the newborn and neonatal seizures. Prevalence rates are unreported, but in one published study, women who received more than 2500mls of water or IV fluids, 26% were hyponatraemic. Oxytocin use may be contributory and accurate fluid balance measurements, vigilance in monitoring of vital signs and timely escalation are important.

Neonatal resuscitation

In 32% of cases, there were problems in neonatal care that contributed to the outcome, half of these in this cohort and others relate to resuscitation.

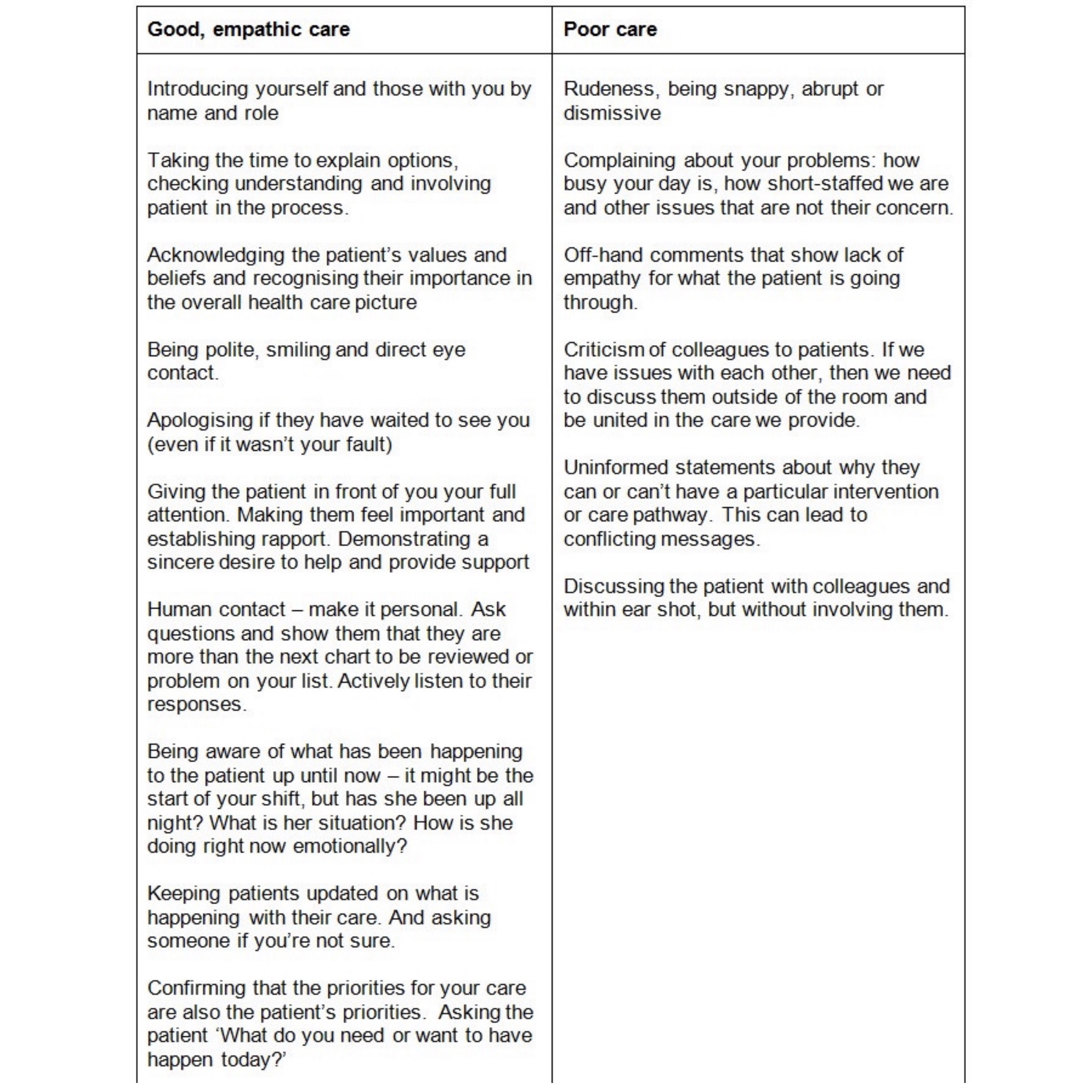

Family apologies and staff support

In this cohort of 92 families, 77% were told by the hospital that an incident had occurred and only 35% were recorded as being offered an apology. The report acknowledges that this low figure is concerning. All NHS organisations are required to comply with what is known as ‘duty of candour’. In Australia, we follow the Australian Open Disclosure Framework (link). Families were invited to be actively involved in the investigation in 30% of cases. The skills needed for these difficult conversations are being addressed in the UK (‘Finding the Words’ workshops) and Australia (Open Disclosure simulation training).

Support for staff occurred in only 49% of investigations and in some cases, the staff involved in providing support were not independent of those carrying out performance reviews. There is compelling evidence that healthcare staff involved in serious incidents are deeply affected. The report recommends an independent package of support be offered to all staff to manage the distress that can be associated - especially for those involved in incidents where possible avoidable harm occurs.

Learning from avoidable brain injuries at birth. Published 25 September 2019

https://resolution.nhs.uk/2019/09/25/learning-from-avoidable-brain-injuries-at-birth/